Ælfric's Maccabees

The story of the Maccabees, a group of Jews who rebelled against the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire in the second century BCE, is recorded in the deuterocanonical books known as 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. These two biblical books recount the rise of Antiochus IV Epiphanes following the death of Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE), the revolt led by the priest Mattathias and his five sons, the martyrdom of Eleazer and the unnamed mother and her seven sons, the military exploits of Judas Maccabeus, and the recapture of Jerusalem in 164 BCE. This was a setting far removed both temporally and geographically from tenth-century Dorset, where Ælfric composed his Lives of Saints (993 x 998). (To read about the Lives of the Saints click here). And yet, there is much in this story that resonates with the other texts in his third collection. From the different strands of this Old Testament history, a narrative emerges that demonstrates the power of faith in the face of pagan aggression, the importance of resistance against cultural and religious oppression, and the legitimacy of war when threatened by hostile invasion. These were all themes of pressing relevance to Ælfric of Eynsham writing at the end of the tenth century. For this was a troubled period, marked by political instability, repeated famine and crop failure, as well as renewed attacks from the Vikings. Within such a context, the addition of two sections on just war and the correct ordering of society provide a fitting conclusion to a complex narrative that celebrates heroism and military prowess, while also emphasizing the importance of the spiritual sustenance provided by the monastic life, which is clearly and firmly distinguished from the duties of those engaged in war.

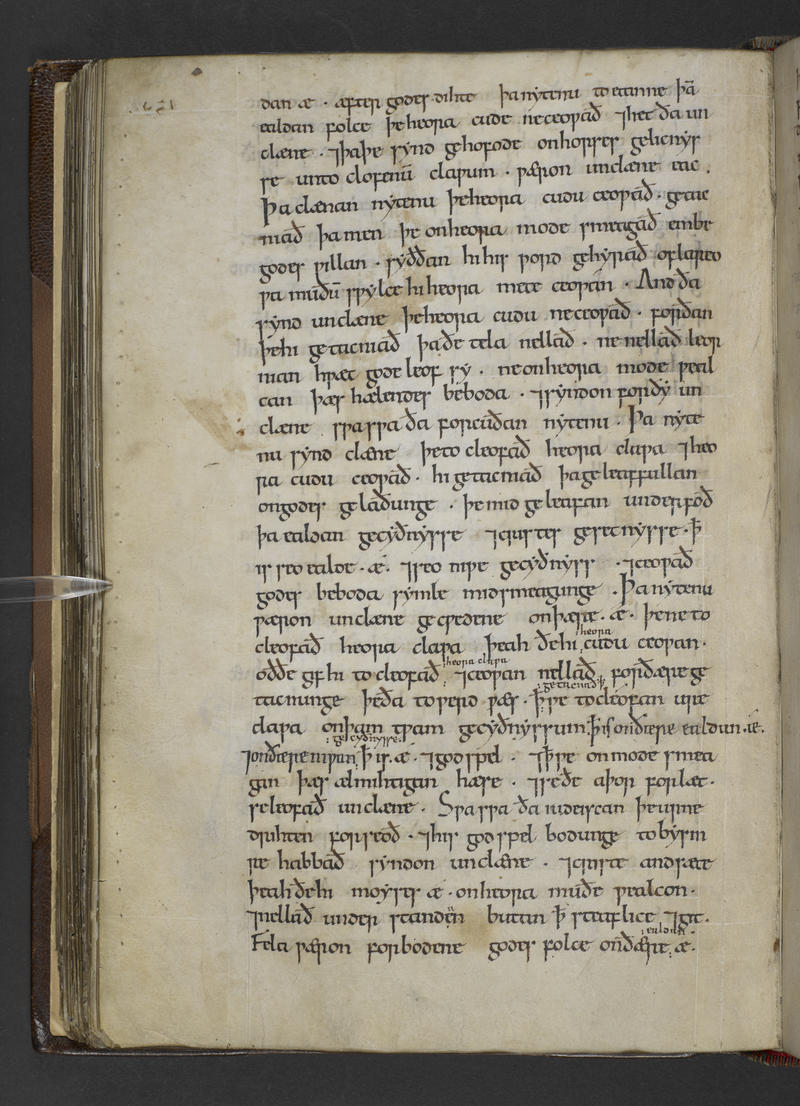

Maccabees is—like most, but not all the texts in The Lives of Saints—composed in Ælfric’s rhythmical prose, a style that relies upon alliteration, rhythm and repetition to create artistic effect. The text is assigned to the kalends of August (that is to say, August 1) in the three manuscripts in which the story is preserved complete and divided into sections by the scribes. In the most complete copy of The Lives of Saints, British Library MS Cotton Julius E.vii, a contemporary corrector has worked on the text, frequently making spelling alterations (such as final -e to -a, in line with standard late West Saxon), as well as adding what appear to have been accidental omissions by the original scribe:

From the British Library Collection: London, BL, MS Cotton Julius E.vii, f. 140v.

The story opens with the death of Alexander the Great and the division of his kingdom under many evil kings:

An ðære cyninga wæs heora eallra forcuðost,

arleas and upp-ahafen, Antiochus gehaten. (Maccabees, 6–7)

[One of these kings was the most wicked of them all, cruel and arrogant, and he was called Antiochus.]

(To listen to a recording of this passage, click here).

In these lines, we can see how Ælfric uses alliteration to create a verbal echo of his message, linking the wicked king Antiochus with the words 'cruel' and 'arrogant' (arleas and upp-ahafen). As is the case throughout The Lives of Saints collection, tyrannical leaders in this text are described in terms that emphasize their anger, scorn and moral impurity, which contrasts directly with the calm impenetrability of the martyrs and saints. The first of these is sum geleafful bocere, har-wencge and eald (‘a faithful scribe, grey haired and old’, 32-3) called Eleazar, who is seized by the king's men and forced to eat food considered treif or unclean. This leads Ælfric into a lengthy digression on the food laws observed by the Jews, as part of which he explains the symbolism of each category of animal, clean and unclean. Eleazar refuses to eat pork or—at the executioners’ suggestion—to pretend to do so, arguing that he is too old to dissimulate, and that deception would be his destruction. In so doing, he is the first of many who mid geleafan his lif geendode (‘ended his life with faith’, 108).

The example of Eleazar is followed by the story of the seven sons, who are tortured and killed for refusing to break the laws commanded by Moses. Each in turn endures horrific mutilation at the hands of the king, but they remain undaunted and compare the actions of their persecutor to the glory they will receive from God:

Ðu, forscyldegodesta cynincg, ofslihst us and amyrst,

ac se ælmihtiga cyning us eft arærð

to þam ecan life, nu we for his æ sweltað. (Maccabees, 132–34)

[You, most guilty king, are killing and destroying us, but the almighty king will raise us up again to the eternal life, because we are dying for his law.]

(To listen to a recording of this passage, click here).

Each of the brothers ends his life with a taunt directed at the king, whose transient earthly power is contrasted repeatedly with the eternal power of the heavenly king. Perplexed, the king suggests to the boys’ mother that she attempt to save her seventh and final son from a cruel death. The woman does as commanded and instructs her son, but not in the way intended. Instead, she encourages him to accept death as his brothers did in the hope of eternal reward; she and the boy are killed and are commemorated with the other brothers on the feast of Lammas day.

The next section, which is labelled De Pugna Machabeorum (‘On the Battles of the Maccabees’) in the badly-damaged manuscript, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius D.xvii, details the rebellion led by Mattathias and his sons, including the great Judas Maccabeus. At their father’s death, Simon is extolled for his wisdom and prudence, but it is Judas who is commended to be their leader in every battle and to avenge his people on ðam fulum hæðenum (‘on the foul heathens’), a typical Ælfrician description of enemies both contemporary and biblical. In his first great battle, Judas defeats Apollonius and his Samarian forces, seizing Apollonius's sword, þæt wæs mærlic wæpn, and he wann mid þam/ on ælcum gefeohte on eallum his life (‘which was a glorious weapon, and he fought with it in every battle for the rest of his life’, 297–98). A series of battles follow, each preceded by speeches and often also by fasting and culminating in victory and glory for God's chosen people. In this section, it is clear that Judas triumphs because of his faith and that Apollonius suffers defeat and an ignominious death because he had treated the Temple contemptuously (l. 543). Yet Ælfric’s attitudes towards the Jews remains ambivalent, as he remarks upon more than one occasion that although they were the dearest to God under the Old Law, it was they who were responsible for Christ’s death (see ll. 515ff. and 552ff.) Still, there is no doubt but that Judas is a great hero, whose physical stature inspires fear and whose stirring speeches rouse even those intending to flee the ravages of the invading army:

Ne gewurðe hit na on life þæt we alecgan ure wuldor

mid earhlicum fleame, ac uton feohtan wið hi,

and gif God swa foresceawað, we sweltað on mihte

for urum gebroðrum, butan bysmorlicum fleame. (Maccabees, 661–64)

[Let it never come to pass in our lifetimes that we lay aside our glory with cowardly flight, but let us fight against them, and if God so ordains, we shall die for our brothers bravely, without shameful flight.]

(To listen to a recording of this passage, click here).

In the final lines of this section, Ælfric quite explicitly claims that Judas Machabeus is to be compared with the saints of the New Testament: he is eall swa halig on ðære ealdan gecyðnysse/ swa swa Godes gecorenan on ðære god-spel-bodunge (‘he is as holy in the Old Testament as God's chosen are in the new dispensation’, 682–83). At the same time, Ælfric is clear that with the New Testament and the coming of Christ, an alternative way was revealed, based upon peace. He discusses the spiritual battle that the good Christian must fight against the enticements of the devil, claiming that the physical battles of the Old Testament prefigure the spiritual battles of the present. That this commentary was intended to be applied to the contemporary situation is clear from the language that Ælfric here uses, when he refers to the causes of just war as the attack of flot-menn (‘seamen’) or other peoples who intend to destroy the land:

Iustum bellum is rihtlic gefeoht wið ða reðan flot-menn

oþþe wið oðre þeoda þe eard willað fordon.

Unrihtlic gefeoht is þe of yrre cymð.

Þæt þridde gefeoht, þe of geflite cymð

betwux ceaster-gewarum, is swyðe pleolic.

And þæt feorðe gefeoht, þe betwux freondum bið,

is swiðe earmlic and endeleas sorh. (Maccabees, 709–15)

[Just war is just war against the fierce seamen or against other peoples who intend to destroy our land. Unjust war is that which derives from anger. The third war, that arises from dispute between citizens, is very dangerous. And the fourth war, which is between kinsmen, is the cause of great misery and endless sorrow.]

(To listen to a recording of this passage, click here).

This is followed by the final story of the piece, in which the priest Onias exemplifies how faith and prayer might overcome military might and unjust attempts to despoil the Temple.

The final and perhaps most famous section of the Maccabees is not part of the story proper, but a tract labelled De tribus ordinibus saeculi (‘On the Three Orders of Society’) in manuscript Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 178, Part I. This is one of two manuscripts in which this section circulated independently of the rest of the text (the other is Oxford, Bodleian Library, Hatton 115). Here, Ælfric follows a scheme used by Alfred and other writers that divides society into those who work, those who fight and those who pray. Of these, unsurprisingly, it is the latter that is Ælfric’s primary concern, because as he claims:

Is nu forþy mare þæra muneca gewinn

wið þa ungesewenlican deofla þe syriað embe us

þonne sy þæra woruld-manna þe winnað wiþ ða flæsclican

and wið þa gesewenlican gesewenlice feohtað. (Maccabees, 824–27)

[The fight of the monks against the invisible devils who lay traps around us is greater now, therefore, than that of the men of the world who fight against human enemies and fight visibly against the visible.]

(To listen to a recording of this passage, click here).

He expands upon this point with specific exempla before returning to his principal message, namely that ‘the servant of God cannot fight with men of the world if he is to have any success in the spiritual fight’ (Se Godes þeowa ne mæg mid woruld-mannum feohtan/ gif he on þam gastlican gefeohte forð-gang habban sceall, 856–57). In this way, he brings to a close a story that has moved from the physical battles of the Jews in second-century BCE Samaria to the spiritual struggles faced by tenth-century monks, creating a sense of continuity and kinship that stretches across historical, linguistic and geographic divides.

Select Bibliography

Editions

Clayton, Mary, and Juliet Mullins, ed. and trans. Old English Lives of Saints, Vol. I–III: Ælfric, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 60 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Lee, Stuart D., ed. Ælfric´s Homilies on Judith, Esther and the Maccabees: An Online Edition. Published 1999: https://users.ox.ac.uk/~stuart/kings/main.htm

Skeat, Walter W., ed. and trans. Ælfric’s Lives of Saints, EETS O. S. 76, 82, 94, 114 (London, 1881-90; repr. as 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966).

Criticism

Halbrooks, J. ‘Ælfric, the Maccabees, and the Problem of Christian Heroism’, Studies in Philology 106 (2009), 263–84.

Jorgensen, Alice, ‘Shame, Disgust and Ælfric’s Masculine Performance’, in Feminist Approaches to Early Medieval English Studies, ed. Robin Norris, Rebecca Stephenson and Renée R. Trilling (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023), pp. 143–68.

Kleist, Aaron J. The Chronology and Canon of Ælfric of Eynsham (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2019).

Magennis, Hugh, and Mary Swan, ed. A Companion to Ælfric (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

Ostacchini, Luisa. Translating Europe in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024).

Pascual, Rafael. ‘Ælfric’s Rhythmical Prose and the Study of Old English Metre’, English Studies 95 (2014), 803–23.

Powell, Timothy E. ‘The “Three Orders of Society” in Anglo-Saxon England’, Anglo-Saxon England 23 (1994), 103–32.

Scheil, Andrew P. ‘Anti-Judaism in Ælfric´s Lives of Saints’, Anglo-Saxon England 28 (1999), 65–86.

Wilcox, Jonathan. ‘A Reluctant Translator in Late Anglo-Saxon England: Ælfric and the Maccabees’, Enarratio 2 (1993), 1–18.

Zacher, Samantha. ‘The Chosen People: Spiritual Identities’, in The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Literature in English, ed. Elaine Treharne and Greg Walker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 457.

Juliet Mullins is an adjunct lecturer and assistant professor in the School of English, Drama and Film and a member of the Humanities Institute, University College, Dublin. She has published on both Early Irish and Old English material. She co-authored with Mary Clayton a new edition and translation of Ælfric’s Lives of Saints for the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library.