Byrhtferth's "Enchiridion"

Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion (OED: Greek ἐγχειρίδιον, ‘handbook’ or ‘manual’) is written in a mixture of Latin and Old English, is preserved in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole 328, and can be dated to the middle of the eleventh century. Its provenance is largely unknown other than it came into the possession of Elias Ashmole sometime in the late seventeenth century, was gifted to the Ashmolean Museum before he died in 1692, and passed to the Bodleian Library in 1860. The Summary Catalogue entry (328, col. 218–219) refers to it as ‘the oldest book in the library’ but other than that its precise origins are a mystery. The manuscript is unique, although small excerpts of it are to be found in Cambridge, University Library, Kk. 5. 32 and Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 421, both from the first half of the eleventh century. It is written on parchment in a brown leather (clasped) binding of 198 x 127mm in size (7.8 x 5 inches) with a writing/parchment space of 160 x 84mm (6.3 x 3.31 inches). Because of its importance, it is on the Bodleian list of restricted manuscripts and can only be viewed at Bodleian Special Collections by special permission. It has been the subject of a considerable amount of scholarly interest and was catalogued by N. R. Ker.

Sadly, despite the importance of the manuscript to computistical studies, it has still not been fully digitised in colour although early (low resolution, monochrome) microfiche is available through Special Collections. Five colour pages (pp. 192–196) are available via Digital Bodleian, and more pages, and the binding, can be viewed on the Flickr pages of Professor Daniel Wakelin (Oxford). It is clearly written and scholars now generally agree that the manuscript was written by a single scribe. The Latin text has been identified by Peter Baker and Michael Lapidge as ‘a late style of Anglo-Caroline minuscule’ and ‘the Old English text’ in ‘Anglo-Saxon set minuscule' which allows for the manuscript to be dated palaeographically (Peter Baker, and Michael Lapidge, eds., Byrhtferth's Enchiridion, Eets S.S. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. cxv–cxvi). Subsequent references to ‘B&L’, and all translations and transcriptions, are from this edition.

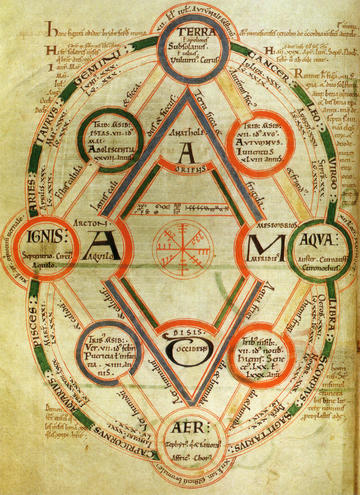

Fig. 1: Byrhtferth: Four elements Terra (Earth), Acqua (Water), Aer (Air), Ignis (Fire) with the zodiac, four cardinal directions and four ages of man. In Latin. MS Oxford St John's College 17, fol. 7v in 1110 or 1111. (Wikimedia Commons)

There are two scholarly editions of the Enchiridion, both published by the Early English Text Society. The first, by Samuel John Crawford, was originally published in 1929, as ‘Part I’ of his Oxford DPhil, and was republished in 1966. It consists of a facing page transcription and translation of the complete text of the Enchiridion but lacks a commentary. ‘Part II’ of his thesis provides more detailed commentary on language, vocabulary, sources, and palaeography, is available for viewing in person via the Bodleian library, but has not yet been digitised. The more modern B&L edition can be described as both seminal and comprehensive comprising a detailed introduction, including history and context of the manuscript, a fully updated edition with facing page translation, and scholarly commentary. It can be considered in isolation because it conflates what is best of Crawford’s originals.

We can attribute the Enchiridion to Byrhtferth (Old English: Byrhtferð) of Ramsey with some certainty because:

Byrhtferth names himself six times, and describes his upbringing at Ramsey Abbey (near modern day Peterborough) as well as his association with Eadnoth, Bishop of Dorchester (1006–16) and formerly abbot of Ramsey (993–1006). He [Byrhtferth] describes himself at one point as a priest, and from numerous passages it is reasonable to infer that he was master at the Ramsey school. (B&L, p. xxvi).

Similarly, we can confidently call the work the ‘Enchiridion’ because that is how Byrhtferth himself refers to it towards the close of Part II: We gesetton on Þissum enchiridion, Þæt ys manualis on Lyden handbóc on Englisc, manega Þing ymbe gerimcræft (‘We have written in this enchiridion – manualis in Latin and handbook in English – many things about computus’, B&L, pp. 120–121).

Scholars generally identify the Enchiridion as a ‘manual’ of computus (the science of the calculation of the date of Easter) and it certainly does contain a significant amount of computistical information. However, much information associated with the Easter calculation is incomplete or only partially explained, Þeah we wace syn and Þas Þing leohtlice unwreon (‘Although we are weak and we explain these things cursorily’, B&L pp. 36-37). It could also be referred to as a ‘text-book’ because, as Faith Wallis suggests in her 2004 (rev. 2012) edition of Bede’s The Reckoning of Time, ‘a textbook […] must have been designed for programmed teaching and learning’. In several places in the Enchiridion, Byrhtferth makes it clear that he is using it as an instructional text:

Ymbe Þa feower timan we wyllað cyðan iungum preostum maÞinga, Þæt hig magon Þe ranclicor Þas Þing heora clericum geswutelian

[We wish to tell young priests more things about the four seasons so that they can more confidently show these things to their clerks.] (B&L pp. 82–83).

So, in this particular example, Byrhtferth was not only using the Enchiridion to teach but also to be used later by others as a more general instructional textbook. This is an idea which gains further credence when we consider that over the course of four Pars (‘Parts’), as well as a discussion of Easter in Part I (IV) and Part III (I) & (II), the Enchiridion also deals with such things as De anno et partibus eius (‘the year and its parts’), De uersibus Bede (‘Bede’s verses’, although these are not necessarily originally from Bede), De Duodecim mensibus (‘The twelve months’), De anno et die nocte et horis et eius partibus (‘The year, the day, the night, the hours and their parts’), De numerorum significationibus (‘On the meanings of numbers’), and De sex aetatibus mundi (‘The six ages of the world’). Along the way, the Enchiridion deals with aspects of grammar, theology, numerology, astronomy, astrology, mathematics, philosophy, meteorology and many other topics too numerous to mention here. Hence, Byrhtferth condenses aspects of Bede’s De Temporibus (‘On times’, c. 703), De natura rerum (‘On the nature of things’, after c. 703) and De temporum ratione (‘The reckoning of time’, c. 722–725), as well as Bede’s theology and grammars, into an Old English vernacular textbook. In fact, outside of Bede, the Enchiridion is a melange of sources, and draws from Helperic’s Liber de Computo, Macrobius’ Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis, Prudentius’ Psychomachia, the Rule of St. Benedict, Abbo for Fleury’s Computus Vulgaris/Ephemeris, and Dionysius Exiguus, Hrabanus, Isidore of Seville, Alcuin, Ælfric’s De temporibus anni, Aldhelm’s De Virginitate and St Jerome amongst many others.

Manuscripts

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole 328

Cambridge, University Library, Kk. 5. 32

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 421

Editions

Baker, Peter, and Michael Lapidge, ed. Byrhtferth's Enchiridion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Crawford, S. J., ed. ‘Byrhtferth's Manual’ (A.D. 1011) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1929).

---. ‘Byrhtferth's Manual, Pt 2.’ unpubl. PhD dissertation, University of Oxford, 1930.

Select Criticism

Baker, Peter. ‘Byrhtferth's Enchiridion and the Computus in Oxford, St John's College 17’, Anglo-Saxon England 10 (2008), 123–42.

---. ‘More Diagrams by Byrhtferth of Ramsey’, in Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge, ed. Katherine O'Brien O'Keeffe and Andy Orchard, 2 vols, Vol. II, Toronto Old English Series (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), pp. 53–73.

---. ‘The Old English Canon of Byrhtferth of Ramsey’, Speculum 55 (1980), 22–37.

---. ‘Studies in the Old English Canon of Byrhtferth of Ramsey.’ unpubl. PhD dissertation (Yale University, 1978).

Berry, R. ‘Ealle Þing Wundorlice Gesceapen: The Structure of the Computus in Byrhtferth's Manual’, Revue de l'Université d'Ottawa 52 (1982), 130–41.

Chiusaroli, F. ‘Costituzione E Impiego Del Lessico Tecnico Nell' Enchiridion Di Byrhtferth: L'ambito Dell'astronomia’, Testi Cosmografici, Geografici Ed Odeporici Del Medioevo Germanico, Atti Del Xxxi Convegno Dell’associazione Italiana Di Filologia Germanica (Aifg) (Louvain la Neuve, France: Fédération Internationale des Instituts d'Etudes M, 2005), 1–39.

Crépin, André. ‘The Transmission of Learning in the Early Middle Ages, Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion’, Caliban: French Journal of English Studies 29 (2011), 21–30.

Fleming, Damian. ‘Hebrew Words and English Identity in Educational Texts of Ælfric and Byrhtferth’, in Latinity and Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature, ed. Rebecca Stephenson and Emily V. Thornbury, Toronto Anglo-Saxon Series (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), pp. 138–57.

Forsey, George Frank. ‘Byrhtferth's Preface’, Speculum 3 (1928), 505–22.

Gorman, Michael. ‘The Glosses on Bede's De Temporum Ratione Attributed to Byrhtferth of Ramsey’, Anglo-Saxon England 25 (1996), 209–32.

Hart, Cyril. ‘Byrhtferth and His Manual’, Medium Avum 41 (1972), 95–109.

Henel, Heinrich. ‘Byrhtferth's Preface: The Epilogue of His Manual?’, Speculum 18 (1943), 288–302.

---. ‘Notes on Byrhtferth's Manual.’ The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 41 (1942), 427–43.

Jones, Charles W. ‘The Byrhtferth Glosses’, Medium Ævum 7 (1938), 81–97.

Ker, N. R. ‘Two Notes on Ms. Ashmole 328 (Byrhtferth's Manual)’, Medium Ævum 4 (1935), 16–19.

Kluge, F. ‘Angelsächsische Excerpte Aus Byrhtferth's Handboc Oder Enchiridion’, Anglia 8 (1885), 298–337.

Lapidge, Michael. ‘Byrhtferth at Work’, in Studies in Medieval English Language and Literature in Honour of Fred C. Robinson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), pp. 25-44.

---. ‘Byrhtferth of Ramsey and the Early Sections of the Historia Regum Attributed to Symeon of Durham’, Anglo-Saxon England 10 (1981), 97–122.

---. ‘Byrhtferth of Ramsey and the Glossae Bridferti in Bedam’, The Journal of Medieval Latin 17 (2007), 384–400.

---, ed. Byrhtferth of Ramsey: The Lives of St. Oswald and St. Ecgwine (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2009).

---. ‘The Library of Byrhtferth’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, ed. Richard Gameson, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 685–93.

Lucas, Robert Anthony. ‘Prolegomena to Byrhtferth's “Manual”’, unpubl. PhD dissertation (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1970).

Smith, Frank Clifton. ‘Die Sprache Der Handboc Byrhtferths Und Des Brieffragmentes Eines Unbekannten Verfassers: Ein Beitrag Zur Lautlehre Des Spätangelsächsischen’, unpubl. PhD dissertation (University of Leipzig, 1905).

Stephenson, Rebecca. ‘Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion: The Effectiveness of Hermeneutic Latin’, in Conceptualizing Multilingualism in England, C.800-C.1250, ed. Elizabeth M. Tyler, Studies in the Early Middle Ages 27 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), pp. 121–44.

---. The Politics of Language: Byrhtferth, Ælfric, and the Multilingual Identity of the Benedictine Reform, Toronto Anglo-Saxon Series (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015).

---. ‘Reading Byrhtferth's Muses: Emending Section Breaks in Byrhtferth's “Hermeneutic English”’, Notes & Queries 54 (2007), 19–22.

---. ‘Saint Who? Building Monastic Identity through Computistical Inquiry in Byrhtferth's Vita S. Ecgwini’, in Latinity and Identity in Anglo-Saxon Literature, ed. Emily V. Thornbury and Rebecca Stephenson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), pp. 118–37.

Whitbread, L. ‘Byrhtferth's Hexameters.’ Notes and Queries 193.22 (1948), 476–76.

Dr Anthony Harris is a fellow of Clare Hall (Cambridge), a visiting fellow of Kellogg College (Oxford), a research fellow of Regent’s Park College (Oxford), and an Associate in Medieval Studies at Harvard University. He completed his MA In English Language and Literature at Oxford, his Masters in Medieval Studies at Reading, and his PhD at Cambridge, all as a mature student. His PhD considered the language of the Enchiridion as well as the early mathematics and astronomy associated with the science of computus. His recent review of Seb Falk’s ‘The Light Ages’ can be found in Peritia, v. 34 (2024), and his article on ‘Beowulf and The Southern Sun (BEOWULF, 603b–06, 1965b–66a)’ in Notes and Queries, 266(3), 245-248. He was also a technical consultant on computus for the ‘Sterne: Das Firmament in St. Galler Handschriften’ exhibition at the Library of St. Gallen in Switzerland. His most recent research considers the use of Generative AI for teaching and researching in the humanities.