Old English Medical Prose

Old English literature is home to a significant body of scientific writing, notably medical texts that reflect the complexity and skill of early medieval learning in England. The most prominent medical collections are found in two manuscripts held at the British Library in London: Royal MS 12 D xvii and Harley MS 585. These date from the tenth and early eleventh centuries and contain extensive treatments for the whole human body. Royal MS 12 D xvii is the oldest surviving vernacular medical codex and comprises Leechbook I, II, and III, named from the Old English word lǽce-bóc, or ‘book of medical remedies’. These books reflect a head-to-toe organisation of ailments, typical of late antique and early medieval medicine, as shown in the introductory remedy:

ON þissum ærestan læcecræftum gewritene sint læcedomas wið eallum heafdes untrymnessum.

[‘In these first remedies, are written treatments against all sicknesses of the head.’]

Royal MS 12 D xvii, fol. 6v

The first two Leechbooks are considered to be a single work: Bald’s Leechbook, named after Bald who was likely its owner. This we can infer from the colophon at the end of Book II, in which the compiler, a certain Cild, is also mentioned:

Bald habet hunc librum cild quem conscribere iussit;

Hic precor assidue cunctis in nomine Xristi.

Quo nullus tollat hunc librum perfidus a me.

Nec ui nec furto nec quodam famine falso.

Cur quia nulla mihi tam cara est optima gaza.

Quam cari libri quos Xristi gratia comit.

[‘Bald owns this book, which he commanded Cild to copy.

I earnestly ask this of everyone in the name of Christ, that no

perfidious person take this book from me

either by force, or by stealth, or by any false speech.

Why? Because the highest treasure is not more dear to me than those dear books

which the grace of Christ brings together.’] (fol. 109v)

Leechbook III is found after the colophon, written in the same hand. It is often viewed as ‘an intentional supplement to existing remedies,’ because it is a shorter compilation, with some remedies mirroring those in Bald’s Leechboook. Nevertheless, numerous recipes are unique and especially valuable for their references to local practices and ingredients, and the inclusion of ailments associated with Germanic cultural beliefs, such as diseases attributed to elves (to listen to a recording of this remedy, click here):

Wið ælfadle: nim bisceopwyrt, finul, elehtre, ælfþonan nioþowearde, and gehalgodes cristes mæles ragu and stor. Do ælcre hand fulle. Bebind ealle þa wyrta on claþe. Bedyp on font wætre gehalgodum þriwa […]. Him biþ sona sel.

[‘Against elf-disease: take betony, fennel, lupin, the lower part of bittersweet nightshade, the lichen from a holy cross and frankincense. Take a handful. Bind all the plants in a cloth. Dip into a fountain with holy water three times […]. They (patients) will soon be well.’] (fol.124r)

This cure illustrates how early English medicine blended herbal medicine with local, culturally-specific beliefs, demonstrating the holistic nature of healing in early medieval England.

The second major manuscript, Harley MS 585, is a smaller, perhaps portable codex. It includes the only extant example of the Lacnunga and the earliest copy of the Old English Herbal and Old English Remedies from Animals, also known as Old English Herbarium Complex. Lacnunga means ‘cures, remedies’ in Old English, and the collection contains nearly two hundred remedies for both humans and animals. Like the Leechbooks, it too follows a head-to-toe arrangement and contains overlapping material. It is, however, distinctive for its rich linguistic variety: Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Old Irish all appear alongside Old English. Additionally, some of its most memorable entries are written in Old English verse and are known as metrical charms, often combining Christian liturgy with traditional ritual practice. The famous Nine Herbs Charm is one such example. It invokes mugwort and eight more plants to drive out poison and disease:

Gemyne ðu, mucgwyrt, hwæt þu ameldodest,

hwæt þu renadest æt Regenmelde.

Una þu hattest, yldost wyrta.

ðu miht wið III and wið XXX,

þu miht wiþ attre and wið onflyge,

þu miht wiþ þa(m) laþan ðe geond lond færð

[‘Remember, mugwort, what you made known

what you disposed at the Solemn Proclamation.

‘Una’ you are called, the oldest of herbs.

You have power against three and against thirty,

you have power against poison and against flying diseases (contagion),

you have power against the loathsome who fares throughout the land.’] (fol. 160r)

In the Charm, the physician utters words over the nine herbs and into the patient’s mouth, ears, and wounds invoking divine protection and healing power. Such words of faith were believed to protect the body and convey blessings to both the speaker and the listener. Oral rituals such as this show the deep belief in the performative power of language, especially when used with faith and authority.

Although the authors of Old English medical texts remain unknown and few medical figures are named, these compilations are far from isolated. They reflect long-standing traditions, drawing particularly on classical medical works of Hippocrates, Galen, Dioscorides, Pliny the Elder, and early Christian thinkers like Isidore of Seville. These sources circulated across Europe, including Italy and France, and were likely known in England well before the tenth century, when these manuscripts were copied. Evidence even suggests that Bald’s Leechbook may have been compiled earlier, possibly during the reign of Alfred the Great (871–899), who is also referenced in Leechbook II: Þis eal het þus secgean Ælfrede cyninge domine helias patriarcha on gerusalem, ‘All this is to be said to King Alfred, ordered Lord Helias, patriarch of Jerusalem.’

The cultural and scholarly interest in medicine intensified during the Benedictine Reform of the tenth and eleventh centuries. Medicine was understood as part of natural philosophy and central to monastic learning, and required knowledge of anatomy and physiology, the properties and therapeutic effects of plants and minerals, bloodletting, and the balance of bodily humours. From Hippocratic-Galenic theory, early medieval English physicians inherited the belief that health depended on the balance of four bodily fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Sickness arose when the humours became imbalanced, and many treatments aimed to correct this, as seen in Bald’s Leechbook remedy:

Nis him blod to lætanne on ædre ac ma hira man sceal tilian mid wyrtdrencum utyrnendum oþþe spiwlum oþþe migolum mid þy þu meaht clænsian þæt omcyn 7 þæs geallan coðe þa readan.

[‘Blood is to be let from a vein but one shall rather treat them with a purgative herbal drink or emetics or diuretics with which you can cleanse the corrupted humour and the red gall-disease.’] (fol. 31r)

In revealing the causes of disease, the nature of the human body as well as the properties of the natural world, medicine offered a deeper understanding of the world and the opportunity to understand God’s creation and theological principles. Indeed, Old English medicine sought to heal not just the body but the soul, blending medical ingredients and liturgical practices, therapeutic instructions and precatory prayers. The middle section of the Lacnunga is dominated by the Lorica of Laidcenn, a litany-like invocation that asks for protection of the whole body against physical and spiritual dangers:

[g]escyld alne mec mid fif ondgeotum

7 mid ten durum smicre geworhtum

þ(æt)te fro(m) þæm hælu(m) oð ðæs heafdes heannesse

nængum lime minum utan innan ic geuntrumige

þylæs of minu(m) mæge lif ascufan

wol[n]es ece adl sar lichoman

[‘protect all of me with my five senses and with my ten skilfully made doors so that from my soles to the top of my head in no members of mine, outside or inside, I may be sick. So that pestilence, weakness, (or) pain cannot thrust the life from my body.’] (fol. 156r)

The five senses are invoked for their shielding powers, while the ten bodily ‘doors’ likely symbolise physical and spiritual perception, acting together to guard the patient from pestilence, death, and the Devil’s enticements. This convergence of body and soul reflects a holistic worldview, where disease was both a physical and moral affliction, calling upon God as both Creator and Physician.

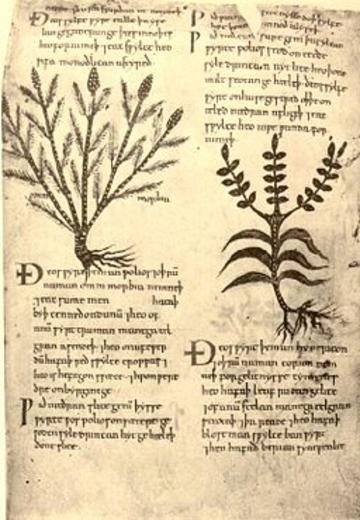

Alongside such remedies, the Old English Herbarium Complex—a translation of Latin sources such as the Pseudo-Dioscorides Herbarius—is an authoritative pharmacology book, offering detailed entries on both herbs and animals and their medicinal properties. The translation is not a unique copy, it is found in three other manuscripts, and one version, British Library, Cotton Vitellius C. iii, is profusely illustrated, and is a testimony to the popularity and wide dissemination of this material.

Cotton Vitellius C iii fol. 74r

A later compilation, Peri Didaxeon, dated to the twelfth century, reflects the ongoing evolution of English medical writing, as it preserves many Old English formulations and recipes alongside Anglo-Norman linguistic elements and bridges the vernacular medical tradition with continental scholasticism and the emerging medical school of Salerno.

While most Old English medical texts are found in manuscripts entirely dedicated to medicine, some are also scattered in other miscellany codices. Collectively, they constitute a rich and remarkable body of texts. Early Medieval England stands out among other contemporaneous European and Germanic cultures for the extent of its vernacular medical production and survival. It was among the first regions to translate medicine from Latin into a vernacular language, reflecting the perceived value of this material and a commitment to availability beyond Latin-literate elites.

Whether through charms, herbal recipes, or humoral theory, Old English medicine offers a compelling lens through which we can not only explore scientific knowledge, but also gain insights into the religious and cultural life of early Medieval England. It includes recipes that reflect popular beliefs, such as elf-diseases, demonic afflictions and loss of cattle. This popular element should not be understood in opposition to the more learned Latin knowledge, but as syncretisms of ecclesiastical belief, medical forms of healing, and folkloric practices, offering a window into how the Anglo-Saxons understood and responded to illness and healing.

Select bibliography

Digitised manuscripts

London, British Library, Royal MS 12 D xvii, iiif.bl.uk/uv/#?manifest=https://bl.digirati.io/iiif/ark:/81055/vdc_100101103280.0x000001

London, British Library, Harley MS 585, https://www.digipal.eu/digipal/manuscripts/996/hands/

British Library, Cotton Vitellius C. iii, iiif.bl.uk/uv/#?manifest=https://bl.digirati.io/iiif/ark:/81055/vdc_100059906235.0x000001

Editions

Cockayne, Thomas O., ed. and trans. Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft of Early England: Being a Collection of Documents, for the most Part Never before Printed, Illustrating the History of Science in this Country before the Norman Conquest. 3 vols (London: Rolls Series, 1864–66).

D’Aronco, M. A., and Cameron, M. L., ed. The Old English Illustrated Pharmacopoeia: British Library Cotton Vitellius C. III, EEMF 27 (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1998).

De Vriend, H. J., ed. The Old English Herbarium and Medicina de Quadrupedibus, EETS OS 286. (London: Oxford University Press, 1984).

Niles, John D., and Maria A. D’Aronco, eds. and trans., Medical Writings from Early Medieval England. Volume 1: The “Old English Herbal,” “Lacnunga,” and Other Texts, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 81 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2023).

Pettit, Edward, ed. and trans. Anglo-Saxon Remedies, Charms, and Prayers from British Library MS Harley 585: The Lacnunga. 2 vols (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001).

Van Arsdall, Anne, ed. Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Early-Medieval Medicine (London, New York: Routledge, 2023).

Wright, Cyril E., ed. Bald’s Leechbook: B.M. Royal MS. 12. D. XVII. EEMF 5 (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1955).

Criticism

Arthur, Ciaran. “Charms”, Liturgies, and Secret Rites in Early Medieval England (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2018).

Batten, Caroline. Health and the Body in Early Medieval England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024).

Beccaria, Augusto. I codici di medicina del periodo presalernitano (secoli ix, x e xi) (Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 1956).

Cameron, Malcolm L. Anglo-Saxon Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Contreni, John J. ‘Masters and Medicine in Northern France During the Reign of Charles the Bald’, in Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom, ed. Margaret Gibson and Janet Nelson (Oxford: BAR Publishing, 1981), pp. 262–82.

D’Aronco, Maria A. ‘How “English” is Anglo-Saxon Medicine? The Latin Sources for Anglo-Saxon Medical Texts’, in Britannia Latina: Latin in the Culture of Great Britain from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century, ed. C. Burnett, N. Mann and W. F. Ryan (London and Turin: Warburg Institute Colloquia 8, 2005), pp. 27–41.

—. ‘Le conoscenze mediche nell’Inghilterra anglosassone’, in International Scandinavian and Mediaeval Studies in Memory of Gerd Wolfgang Weber, ed. Michael Dallapiazza, Olaf Hansen, Preben Meulengracht Sorensen and Yvonne Bonnet (Trieste: Edizioni Parnaso, 2000), pp. 129–46.

Doyle, Conan. The Reception of Latin Medicine in Early Medieval England: The Evidence from Old English Texts (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2025).

Glaze, Eliza F., and B. K. Nance. Between Text and Patient: The Medical Enterprise in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Firenze: SISMEL-Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2011).

Glick, Thomas F., Steven J. Livesey and Faith Wallis. Medieval Science, Technology and Medicine: An Encyclopedia (London: Routledge, 2017).

Hall, Alaric. Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2007).

Harrison, F., A. E. L. Roberts, R. Gabrilska, K. P. Rumbaugh, C. Lee and S.P. Diggle. ‘A 1,000-year old Antimicrobial Remedy with Antistaphylococcal Activity’, mBio 6. No. 4 (2015), http://mbio.asm.org/content/6/4/e01129-15.

Hughes, Muriel J. Women Healers in Mediaeval Life and Literature (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries, 1943).

Jolly, Karen L. Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

Kesling, Emily. Medical Texts in Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2020).

Leja, Meg. ‘The Sacred Art: Medicine in the Carolingian Renaissance’, Viator 47 (2016), 1–4.

Maion, Danielle. ‘Il trattato medico antico inglese ‘Peri Didaxeon’: problemi di traduzione’, Traduzione, società e cultura 10 (2002), 1–29.

Meaney, Audrey L. ‘Variant Versions of Old English Medical Remedies and the Compilation of Bald’s “Leechbook”’, Anglo-Saxon England 13 (1984), 235–68.

—. ‘The Anglo-Saxon View of the Causes of Disease’, in Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, ed. S. Campbell, B. Hall and D. Klausner, 12-44 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992).

Pucci-Donati, Francesca. Dieta, salute, calendari: Dal regime stagionale antico ai regimina mensium medievali: origine di un genere nella letteratura medica occidentale (Spoleto: Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo, 2007).

Scragg, Donald G., ed. Superstition and Popular Medicine in Anglo-Saxon England (Manchester: Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, 1989).

Tracy, Larissa, and Kelly DeVries. Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

Van Arsdall, Anne. 'Rehabilitating Medieval Medicine', in Misconceptions About the Middle Ages, ed. Stephen Harris and Bryon L. Grisby (New York, London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 135–41.

Voth, Christine, ed. Cultivating the Earth, Nurturing the Body and Soul: Daily Life in Early Medieval England. Essays in Honour of Debby Banham (Turnhout: Brepols, 2025).

Wallis, Faith. ‘Medicine and the Senses: Feeling the Pulse, Smelling the Plague, and Listening for the Cure’, in A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages, 500–1450, ed. Richard Newhauser (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), pp. 131–52.

Wickersheimer, Ernest. Les manuscripts latins de la médecine du haut moyen âge dans les bibliothèques de France (Paris: Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1966).

Irene Tenchini completed her PhD at Queen’s University of Belfast, focusing on literary and linguistic representations of taste and smell in Old English medical collections and religious poetic texts. She has published on weather and the senses in Old English medicine, and she is now working on the cultural heritage of taste, smell, and touch in a selection of early English manuscripts produced during the Benedictine Reform.