Wonders of the East

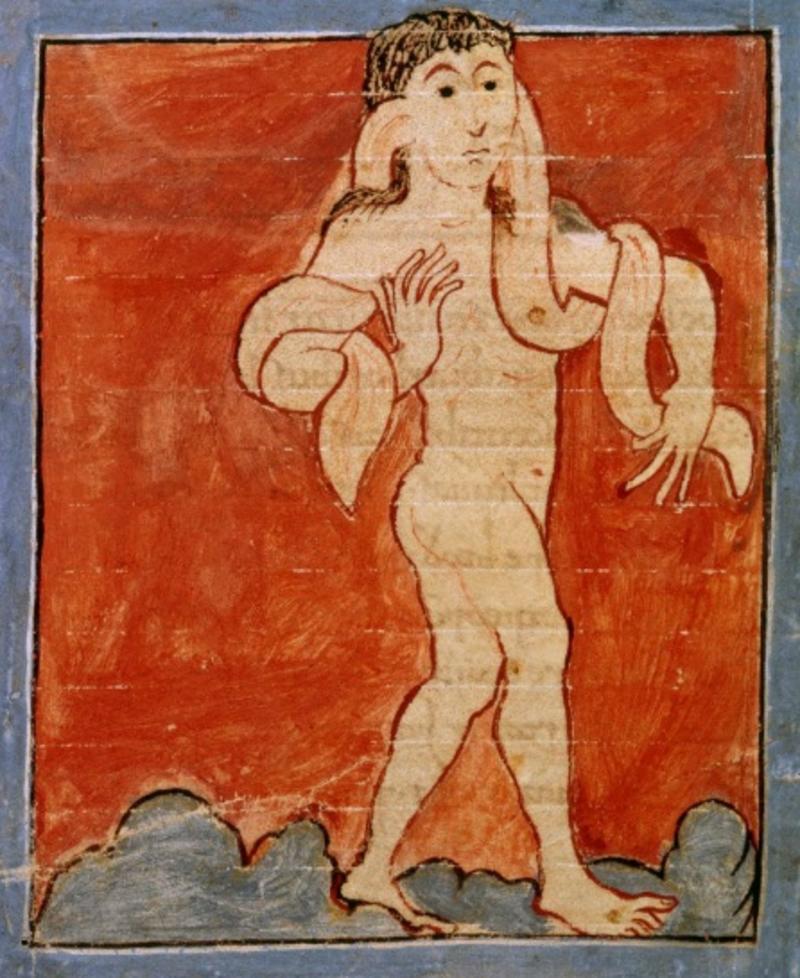

The Panotii: British Library, Cod. Cotton Tiberius B V, 83v. (circa 1040)

The texts and images now called either the Wonders of the East or the Marvels of the East are catalogs of creatures and phenomena of the mythical/natural world associated, for the Early English, with “the East,” a vague geographical area containing West and South Asia and North Africa. As such, of course, they are also associated with ideas of who the non-Eastern readers/viewers of these texts thought themselves to be. Some of these creatures are recognizable: sheep, pepper plants, an oyster-eating bishop. Some are recognizable with unusual, exaggerated, or frightening customs, features or abilities: men that eat raw fish, chickens that can set people on fire. Many fall into the category of the monstrous: hybrid creatures or creatures whose bodies are otherwise marked by the excess, lack or displacement associated with the monstrous: people with their heads on their chests, or with two heads, or with boar’s tusks and ox tails:

Ðonne syndan oþere wif þa habbað eoferes tuxas ⁊ feax oð helan side. ⁊ oxan tægl on lendunum. Þa wif syndon þryttyne fota lange ⁊ hyra lic bið on marmorstanes hiwnesse ⁊ hi habbað olfendan fet ⁊eoseles teð of hyra micelnesse hy gefylde wæron frō þæm miclan macedoniscan alexandre þa cwealde he hy þa he hy lifiende oferfon ne mehte for þon hy syndon æwisce on lichoman ⁊ unweorþe. (Mittman and Kim, 50-51)

[Then there are other women who have boar’s tusks and hair to their heels and ox’s tails on their loins. These women are thirteen feet tall, and their bodies are the color of marble, and they have camel’s feet and ass’s teeth. Because of their greatness, they were killed by the great Macedonian, Alexander. He killed them when he could not capture them alive, because their bodies are shameless and contemptible.] (Mittman and Kim, 70-71)

London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv: The Wonders of the East, fol. 8v (Women with boars' tusks)

The Wonders/Marvels draw on a series of ancient sources, as traced by Rudolf Wittkower in 1942. These include popular Greek and Roman authors, such as Herodotus and Pliny the Elder, earlier medieval authors, especially Isidore of Seville, and less well-known figures, such as Scylax of Caryanda, Ctesias of Cnidus, and Megasthenes, whose works are known only through quotations in the works of other authors. Wittkower traces some of the wonders further back to ancient Indian epics that these Greek authors were familiar with. There are many competing theories about the textual source of the Old English text. An early theory from Kenneth Sisam was that the Old English translation was probably made at some point in the late ninth or early tenth century by a Mercian author who used the Latin Letter to Fermes to the Emperor Hadrian (itself a translation of Greek original) as their main source.

There are three manuscripts of the Wonders/Marvels, all of which are heavily illustrated, which suggests that visual representation is fundamental to what this text is doing. The manuscripts vary greatly in style. The provenance of these manuscripts has been much debated without any conclusive evidence or thoroughly convincing argument. The earliest is one of five texts contained in the Beowulf Manuscript (London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, ca. 1000; all folios are online in the e-book of Mittman and Kim, 2012[1] , and several in Mittman and Kim, 2010[2] , 2023[3] ). Its images are loosely outlined and filled with gentle ink washes.

British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv fol. 101r: Wonders of the East (three dog like ants attacking a tethered camel man in a tunic), via wikicommons

The second is in a complex miscellany containing geographical, scientific, calendrical, and other materials (London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v, ca. 1025; several images are online in Kim and Mittman, 2010, 2023):

London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r (a blemmyae); © British Library Board.

London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r (a blemmyae); © British Library Board. London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r (a blemmyae); © British Library Board.

London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r (a blemmyae); © British Library Board.

London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82r (a blemmyae); © British Library Board.

The most recent manuscript of Wonders is housed with a calendar and astronomical materials (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 614, ca. 1120–1140).

Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Shelfmark: MS Bodleian 614, fols 39v–40r (wikicommons)

The images from the latter two are firmly outlined and fully painted in tempera. The images in all three provide a wealth of details that contrast with, augment, contradict and otherwise interact with the text and the text’s verbal descriptions in provocative ways. The text in the Beowulf manuscript is written in Old English. The text in Tiberius B.v occurs in both Latin and Old English, and includes a number of entries, most notably the story of Iamnes and Mambres, which do not occur in other versions. The Bodley 614 text is in Latin alone, and adds a dozen more entries.

It is impossible to provide a summary of the plot of the Wonders/Marvels, because the overall movement of the text is not narrative. For example, the text frames the descriptions of wonders with distance markers from one location to another, and in two different units of measurement. But those two different units of measurement vary considerably in proportion to one another, and, even disregarding that difficulty, charting the course from one location to another in the text yields a vertiginous and infolded path with no clear trajectory. Individual portraits within the text, however, often include short narratives. The gold-mining ants as big as dogs, for example, are presented as part of a description for how a daring man might rob these creatures of their gold.

The Donestre is presented as a creature like a man from the waist down and like something else from the waist up:

Ðon [is s]um ealond in þære readan sæ þær is mancyn þæt is mid us donestre nemned. Þa syndon geweaxene swa frifteras fram þam heafde oð ðone nafolan ⁊ se oðer dæl bið mennisce onlic. ⁊ hy cunnon mennisce gereord þonne hy fremdes cynnes mannan geseoð þonne nemnað hy hyne ⁊ his magas cuþra manna naman ⁊ mid leaslicum wordum hy hine beswicað ⁊ hine gefoð ⁊ æfter þan hy hine fretað ealne butan þon heafde ⁊ þonne sittað ⁊ wepað ofer þam heafde. (Mittman and Kim, 54-55)

[Then there is a certain island in the Red Sea where there is a race of people that is, among us, called Donestre. They are grown like soothsayers from the head to the navel, and the other part is like a human, and they know human speech. When they see a person of foreign race they call out to him and his kinsmen the names of familiar men and with false words they seduce him and seize him and after that they eat him, all except the head. And then they sit and weep over that head.] (Mittman and Kim, 66-67)

The Wonders occurs in the Beowulf manuscript in the same hand as the Letter of Alexander to Aristotle. However, although the Wonders material overlaps with the Alexander material, and Alexander is mentioned in a number of episodes (the generous men Alexander praised, the monstrous women he killed …), the Wondersdiffers from the Alexander material in its stubbornly de-centered presentation: this is not a travel narrative exactly, nor epistolary, nor a likely candidate for development into romance. While the Wonders is clearly cousin to the bestiary, it does not allow for any coherent moral or religious allegory. Yet its inclusion in both the scholarly miscellany of Tiberius B.v, and the Beowulf manuscript, with its range of Old English prose, poetry, and texts explicitly Christian and otherwise, as well as what Kenneth Sisam called its ‘special interest in monsters’, suggests that the Wonders allowed for congruence with a range of literary and scholarly concerns as well as a number of different readerships in the early English period.

The wonders vary quite widely, but share a loose organizing principle: contrast with the reader’s geography, landscape, natural environment, body, and behaviors. The text makes this contrast explicit by repeatedly evoking a sense of shared community with the reader through the use of first-person plurals: “hens like our own red hens”; “a race of people that is, among us, called […]”. Their points of difference work collectively to construct an image of the English reader/viewer as that which is unlike these distant wonders in a great many ways. Still, this over-asserted difference periodically erodes; what might sound at first like points of difference often collapse upon closer inspection, turning the Wonders into a source of as much anxiety as comfort.

Select Bibliography

Editions and translations

Fulk, R. D., ed. and trans. The Beowulf Manuscript, Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 3 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 15–31.

Malone, Kemp. The Nowell Codex (British Museum Cotton Vitellius A. XV, Second Manuscript), Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile 12 (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1963).

McGurk, P., David N. Dumville, Malcolm R. Godden, and Ann Knock, eds. An Eleventh Century Anglo-Saxon Illustrated Miscellany: British Library Cotton Tiberius B.v Part I together with leaves from British Library Cotton Nero D.ii, Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile 21 (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1983).

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), pp. 175–203 [Latin and Old English text and translation].

Secondary Reading

Ford, Alun. J. Marvel and Artefact: The “Wonders of the East” in its Manuscript Contexts (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

Friedman, John Block. The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1981).

Hurley, Mary Kate. ‘Distant Knowledge in the British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.V Wonders of the East’, The Review of English Studies 67, no. 282 (2016), 827–43.

Kim, Susan M., and Asa Simon Mittman. ‘Ungefrægelicu deor: Truth and the Wonders of the East’, Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010), available online: https://doi.org/10.61302/TJOI9538.

———. ‘The Skin We Stand On: Landscape-Skinscape in the Tiberius B.v Marvels of the East’, Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 9 (2023), available online: https://doi.org/10.61302/NQTB9141.

Mittman, Asa Simon. Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, revised 20th Anniversary edition (Abingdon: Routledge, 2026, forthcoming).

Mittman, Asa Simon, and Susan M. Kim. Inconceivable Beasts: The Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript (ACMRS/Brepols, 2013), available online: https://doi.org/10.17613/qj8hw-4w097.

Mittman, Asa Simon, and Susan M. Kim. ‘Anglo-Saxon Frames of Reference: Framing the Real in the Wonders of the East’, Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010): https://doi.org/10.61302/LNHO7205.

Orchard, Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995).

Oswald, Dana M. Monsters, Gender and Sexuality in Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2010).

Sisam, Kenneth. ‘The Compilation of the Beowulf Manuscript’, in his Studies in Old English Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953), pp. 65–97.

Wittkower, Rudolf. ‘Marvels of the East: A Study in the History of Monsters’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942), 159–97.

Asa Simon Mittman (Professor of Art & Art History, California State University, Chico), is author of Cartographies of Exclusion: Anti-Semitic Mapping in Medieval England (2024) and Maps and Monsters in Medieval England (2006, revised second edition 2026), co-author with Susan Kim of Inconceivable Beasts: The Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript (2013), and author and co-author of many articles on monstrosity and marginality in the Middle Ages, including pieces on race and anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages. His collaborative From Local to Global: Maps and Mapmaking during the Middle Ages is under contract with Cambridge University Press.

Susan M. Kim (Professor Emerita, Department of English, Illinois State University) is the co-author, with Asa Simon Mittman, of Inconceivable Beasts: the Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript (2013), and the author or co-author of many chapters and articles on monstrosity and representation. Related publications include the co-edited volumes A Material History of Medieval and Early Modern Ciphers: Cryptography and the History of Literacy (2018) and Collaborative Humanities Research and Pedagogy: The Networks of John Matthews Manly and Edith Rickert (2022). She is the co-author of This Language, a River (second edition forthcoming in 2026).