Wulfstan's "Institutes of Polity"

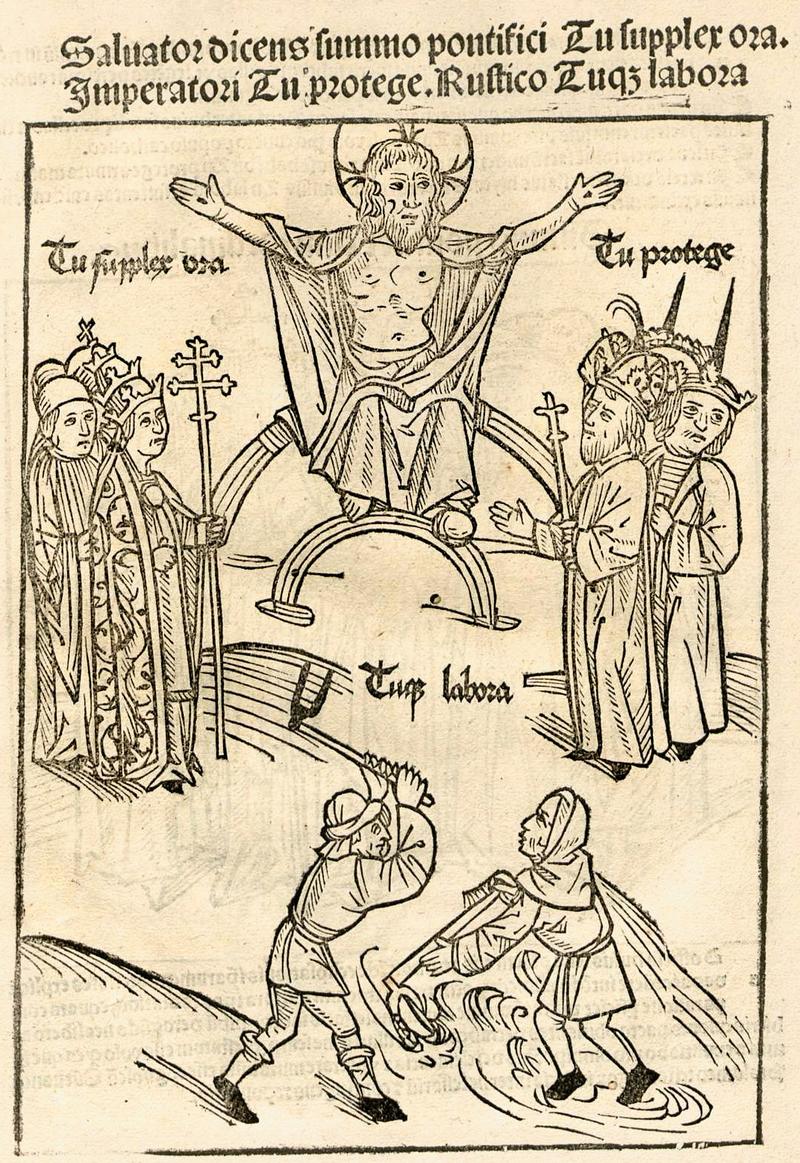

Anon. artist; from Prognosticatio by Johannes Lichtenberger., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Institutes of Polity is the name given to several nebulous collections of chapters outlining the duties of the various ranks of late Anglo-Saxon society, attributed to Archbishop Wulfstan of York (d. 1023). Although Wulfstan is mostly remembered by literary historians for his fire-and-brimstone sermons and by legal historians for his law codes, he also wrote letters, Latin sermons, poems, chronicle entries and several other works which defy classification. It is into this perplexing final category that we must place Polity. The most satisfactory classification might be to call it ‘estates literature’, a tradition dating back to St Paul, which sets out the duties of each rank of society.

This difficulty in classification is only exacerbated by the complex relationship of the surviving versions of Polity. The Polity we encounter in medieval manuscripts is much more slippery and fascinating than its slightly dry editorial title suggests. The versions vary from manuscript to manuscript, as does the order of the chapters. These chapters are usually interspersed throughout their manuscripts with other material in-between. Therefore, it is not clear to what extent we should even understand Polity as a single text. As if to compound the confusion, Wulfstan frequently recycles his own work and as a result many passages from Polity are also found in his law codes and homilies. Because of this complexity, it is useful to begin by explaining both the editorial history and the manuscript reality of Polity, before looking more closely at the texts themselves.

The first print edition was by David Wilkins, published in 1721. In his edition, Wilkins did not treat the chapters of Polity as a single text. Benjamin Thorpe was the first to do so in his edition of 1840. In 1918, Karl Jost demonstrated for the first time that these chapters were the work of Wulfstan. Jost was also the first to propose that the text should be divided into two stages of development. He argued that the first stage took place during the turbulent reign of Æthelred II (known to history as ‘the Unready’) and that a later stage took place following the conquest of Cnut (one of only two English monarchs to be given the epithet, ‘the Great’). Jost labelled these stages I Polity and II Polity and published an edition which used this division in 1959. The most recent edition of Polity is by Andrew Rabin, in Old English Legal Writings, published in 2020 with a facing-page translation. Rabin maintains the I and II Polity division. All further quotations are taken from Rabin’s edition of II Polity unless otherwise stated.

The main versions of Polity survive in three manuscripts. The version on pp. 86–93 of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 201 is what Jost calls I Polity (the first stage, developed under Æthelred). An intermediate stage is found in London, British Library MS Cotton Nero A. i. The early I Polity occupies folios 70r– 76v, but further material is found throughout the manuscript. Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 121 contains a version scattered throughout the manuscript, which combines material found in both CCCC 201 and Nero A.i. This version Jost calls II Polity (the later stage, developed under Cnut). Jost viewed this is the most complete version of Polity. Additionally, a fragmentary version of this text is found in Cambridge, University Library, Additional 3206.4. Two homilies based on Polity can also be found in London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius A. iii.

The version found in Junius 121 is favoured for modern editions of II Polity and is still held up as the closest to Wulfstan’s final vision for the text. This version postdates Wulfstan’s lifetime and has been substantially reordered and interspersed with other texts, some of which are by Wulfstan (e.g. Canons of Edgar and the Benedictine Office). It is common editorial practice to use the text of the version found in Junius 121, but to reorder the chapters. In recent years, some scholars have questioned the value of the I and II Polity editorial approach, arguing that the complexity of the manuscript witnesses does not support such a clear-cut differentiations between two reconstructed texts. For example, in Junius 121, the text begins with a chapter on God, the heavenly king (Be heofenlicum cyninge) and ends with a chapter on all Christian people (Be eallum cristenum mannum). CCCC 201 and Nero A. i both instead begin with the earthly king (Be cinincge and Be cynge respectively) and the former ends with all Christian people (Be eallum cristenum mannum). The ending of the version in Nero A. i depends entirely upon where one decides to draw a line between texts and could be Be eallum cristenum mannum (75v–76v), Item. Biscopas (97v–98v), or Be eorðlicum cyninge (120r). Nero A.i is the only version which contains Wulfstan's own hand, and it is here that we can most obviously see him revising Polity.

Whether one reads Polity in its knotty, non-linear original forms or in a straightened-out modern edition, it is still almost impossible to know what kind of text it is or what its purpose might have been. The division of Polity into chapters gives it the appearance of a law code, but the content is clearly quite different. The style is typical of Wulfstan, but the text is evidently not a sermon or homily. Wulfstan and his scribes give no clue as to the text's purpose: all of the surviving variants are presented without titles, only the rubrics which begin each section.

Although it does so in a very different way, Polity calls for the kind of reform that we see in Wulfstan’s more famous works, such as the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos. Rather than haranguing an audience, however, Politycomprehensively outlines an ideal Christian society, one rank at a time. It also points out the flaws of the current society. The better, holier society might not be some distant and unattainable dream, but a much-improved version of the one Wulfstan existed within. Or perhaps, it would be more accurate to say that Polity outlines a society which has not slipped as far from God’s ideal. To give an idea of exactly how Wulfstan describes this society, I have selected several extracts from different sections of Polity below.

Be cynestole (‘Concerning the Throne’)

In II Polity, Be cynestole follows sections on God, the King and kingship. The opening of this section is known for its elaboration of the ‘three orders’:

Ælc riht cynestol stent on þrym stapelum, þe fullice ariht stent. An is oratoresand oðer is laboratores; and ðridde is bellatores. Oratores sindon gebedmen þe Gode sculan þeowian and dæges and nihtes for ealne þeodscipe þingian georne. Laboratores sindon weorcmen þe tilian sculon þæs ðe eall þeodscype big sceall liban. Bellatores syndon wigmen þe eard sculon werian wiglice mid wæpnum. On þyssum ðrym stapelum sceall ælc cynestole standan mid rihte on Cristenre þeode. (§6, ll. 1–9)

[Each just throne that stands fully as it should rests upon three pillars: first, those who pray; second, those who labour; and third, those who fight. Those who pray are the clergy, who must serve God and fervently plead for all people day and night. Those who labour are the workers who must toil for that by which the entire community may live. Those who fight are the warriors who must protect the land by waging war with weapons. On these three pillars must each throne stand in a Christian polity.]

The ‘three orders’ are presented close to the beginning of Wulfstan’s description of an ideal society, but he was not the first to invoke this concept in an Old English context. The concept is briefly mentioned in the Old English translation of Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy, but in his evocation of the concept in Polity, Wulfstan recycles a passage from Ælfric of Eynsham's Letter to Sigeweard. The passage is reused almost word for word, but—amongst other changes—Wulfstan reorders the list, so that oratores (‘those who pray’) come first. This small alteration aligns well with the prominence given to bishops and priests throughout Polity. Wulfstan reused not only passages from Ælfric, but sometimes entire homilies. As we shall see elsewhere in Polity, Wulfstan is willing to reuse not only the work of others, but also his own compositions.

Be ðeodwitan (‘Concerning Councillors’)

Wulfstan lists all the nation's councillors, who are responsible for steering the country in the right direction:

Cyningan and bisceopan, eorlan and heretogan, gerefan and deman, larwitan and lahwitan (§7, ll. 1–2)

[Kings and bishops, nobles and generals, reeves and judges, the learned and the legal councillors.]

First and foremost amongst the advisors are the bishops. It is important to the subtle pairing of Cyningan and bisceopan (‘kings and bishops’) which begin Wulfstan’s list. This section, which ostensibly covers the duties of all councillors, is concerned primarily with the duties of bishops. The importance of bishops amongst councillors due to their status as messengers of God is repeatedly emphasised by Wulfstan. It is the bishops who will bring God’s law to England:

And bisceopas syndon bydelas and Godes lage lareowas, and hi sculan riht bodian and unriht forbeodan. And se þe oferhigoge þæt he heom hlyste hæbbe him gemæne þæt wið Gode syflne. And gif bisceopas forgymað, þæt hi synna ne styrað ne unriht forbeodaþ ne Godes riht ne cyþað, ac clumiað mid ceaflum, þær hi sceoldan clypian, wa heom þære swigean (§7, ll 4–10).

[And bishops are the messengers and teachers of God‘s law, and they must proclaim justice and forbid injustice. And anyone who disdains to listen to them make take issue about that with God himself. And if bishops fail by not curbing sin or forbidding injustice or making known God’s law, but by mumbling with their mouths when they should shout, woe to them for that silence!]

It is incumbent upon the bishops to use their prominent place in society to preach the Gospel, but it is perhaps even more important that they uphold God’s law. Wulfstan trusts the bishops much more fully than other councillors and beseeches them to keep their secular counterparts in check.

Item de episcopis [‘Likewise, Concerning Bishops’]

By this point in Polity, the centrality of bishops to Wulfstan’s project of reform can be in no doubt. But their importance is further evidenced by the twenty-seven chapters devoted to their duties. In Nero A.i we can see that Wulfstan’s hand is particularly attentive to the section on bishops. Many of the solemn duties found in the section on councillors are restated, but Wulfstan takes the opportunity to offer an additional warning to those who would ignore the teachings of his bishops:

Eala, fela is swaþeah þæra þe hwonlice gymað and lythwon reccað embe boca beboda oððe bisceopa lara: and eac embaæ bletsunga oððe unbletsunga leohtlice lætað, and na understandaþ swa swa hy sceoldan, hwæt Crist on his godspelle swutollice sæde, þa þa he þus cwæþ: Qui vos audit, et reliqua. Et item: Quocumque ligaveritis et cetera. Et item: Quorum remiseritis peccata, remittuntur eis, et cetera. Alibi etiam scriptum est: Quodcumque benedixeritis, et cetera. Et psalmista terribiliter loquitur dicens: Qui noluit benedictionem, prolongabitur ab eo. Swylc is to beþencenne and wið Godes yrre to warnienne symle. (§11, ll. 1–13).

[Sadly, there are nonetheless many of those who lightly regard and little heed the precepts of the books and the teachings of the bishops; and also frivolously ignore blessings or curses, and do not understand as they should what Christ in his Gospel clearly said when he spoke thus: He that heareth, etc. And likewise: Whatsoever thou shalt bind, etc, etc. And likewise: Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven them, etc. Elsewhere too it is written: Whatever you have blessed, etc. And the psalmist, speaking chillingly, says: he would not have a blessing, and it shall be far from him. This is to be reflected upon and the wrath of God always to be shielded against.]

Wulfstan is happy to slip into a sermonising tone throughout Polity, but this passage which closes his first section on bishops (not counting the councillors section) is his longest Biblical digression in Latin. It is almost as if he ends his statement of a bishop’s duties with a practical demonstration of how a best to carry out these duties, through the delivery of a brief sermon. But rather than offering any interpretation of the Latin passages, he issues a challenge to reflect on the words of Christ: thus, passing on the work of interpretation to the addressee.

Be eallum Cristenum mannum (‘Concerning all Christian People’)

Wulfstan ends Polity by expanding his address to include all Christian people. In the final passage, Wulfstan includes himself as part of this group through his use of the pronoun, 'we':

Utan þæt geðencan oft and gelome and georne gelæstan þæt þæt we behetan þa we fulluht underfengan, ealswa us þearf is. (§33, ll. 1–3)

[Let us reflect upon this repeatedly and sincerely abide by that which we promised when we received baptism, just as is our obligation.]

This exhortation is part of a longer passage which is almost identical to that which ends Wulfstan´s most famous work, the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos. A section of the Sermo passage can be found in its ROEP introduction, but it is worth including again here:

beorgan us georne wið þone weallendan bryne helle pites, ⁊ geearnian us þa mærþa ⁊ þa myrhða þe God hæfð gegearwod þam þe his willan on worolde gewyrcað. God ure helpe. Amen. (ll. 207–211).

[[let us] protect ourselves zealously from the surging fire of hell-pits and secure for ourselves the glories and the joys which God has prepared for those that work His will in the world. May God help us. Amen.]

The similarity is clear when compared with the final lines of Polity:

beorgan us georne wið þone weallendan byrne hellewites, and geearnian us ða mærða and ða myrhða, ðe God hæfð gegearwod þam ðe his willan on worulde gewyrcað. Amen. (§33, ll. 6–9).

[[let us] protect ourselves zealously from the surging fire of hellish torment and secure for ourselves the glories and the joys which God has prepared for those that work His will in the world. Amen.]

The first difference is the danger of helle pites (‘hell-pits’) in the Sermo as opposed to hellewites (‘hellish torments’) in Polity. This might simply be due to an accident of copying in either direction, as p and w have a very similar appearance in an insular hand, because the wynn (ƿ) letterform was used for the w sound. The second difference is the Sermo’s direct call for God’s help, not present in Polity. This could have been added due to the particularly desperate times in which it was preached. Such reuse is typical of Wulfstan: if he found or composed a passage that he liked, he would usually use it more than once but would never stop reworking the text.

Bibliography

Manuscripts

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College (pp. 86–93)

Cambridge, University Library Additional MS 3206 (fragment)

London, British Library, MS Cotton Nero A.i (ff. 70r–76v, 97v–98v, 102r–109v, 120r)

London, British Library MS Tiberius A.iii (ff. 93r–93v)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Junius 121 (ff. 9r–13v, 15r–15v, 17r-19v, 20v–23v, 32v–34r, 57v–59r)

Editions

Jost, Karl, Die “Institutes of Polity, Civil and Ecclesiastical”: Ein Werk Erzbischof Wulfstans von York, Schweizer anglistische Arbeiten / Swiss Studies in English, 47 (Bern: Francke, 1959).

Rabin, Andrew, ed. and trans., Old English Legal Writings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020).

———, ed. and trans., The Political Writings of Archbishop Wulfstan of York, Manchester Medieval Sources(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015) (translation only).

Thorpe, Benjamin, Ancient Laws and Institutes of England (London: G. E. Eyre and A. Spottiswoode, 1840).

Wilkins, David, ed., Leges Anglo-Saxonicae Ecclesiasticae et Civiles (London: William Bowyer, 1721).

Secondary

Atherton, Mark. ‘Cambridge Corpus Christi College 201 as a Mirror for a Prince? Apollonius of Tyre, Archbishop Wulfstan and King Cnut’, English Studies, 97 (2016), 451–72.

Bethurum Loomis, Dorothy. ‘Regnum and Sacerdotium in the Early Eleventh Century’, in England Before the Conquest: Studies in Primary Sources Presented to Dorothy Whitelock, ed. Peter Clemoes and Kathleen Hughes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp. 129–46.

Crișan, Andrei. ‘The Modular Structure of Wulfstan’s Institutes of Polity: Discarding Jost’s “I Polity” and “II Polity”’, Notes and Queries, 72 (2024), 139–41.

Hollis, Stephanie. ‘“The Protection of God and the King”: Wulfstan’s Legislation on Widows’, in Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: The Proceedings of the Second Alcuin Conference, ed. Matthew Townend (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), pp. 443–60.

Jost, Karl. ‘Review of Bernhard Fehr, Die Hirtenbriefe Ælfrics’, English Studies 52 (1918), 105–12.

Ker, N. R. ‘The Handwriting of Archbishop Wulfstan’, in England Before the Conquest: Studies in Primary Sources Presented to Dorothy Whitelock, ed. Peter Clemoes and Kathleen Hughes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp. 315–31.

Reinhard, Ben. ‘Cotton Nero A.i and the Origins of Wulfstan’s Polity’, Journal of English and Germanic Philology 119 (2020), 175–205.

———. ‘Wulfstan and the Reordered Polity of Cotton Nero A. i’, in Law | Book | Culture in the Middle Ages, ed. Thom Gobbitt (Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 51–70.

Townend, Matthew, ed. Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: The Proceedings of the Second Alcuin Conference, Studies in the Early Middle Ages 10 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004).

Trilling, Renée R. ‘Sovereignty and Social Order: Archbishop Wulfstan and the Institutes of Polity’, in The Bishop Reformed: Studies of Episcopal Power and Culture in the Central Middle Ages, ed. John S. Ott and Anna Trumbore Jones (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 58–85.

Whitelock, Dorothy. ‘Archbishop Wulfstan, Homilist and Statesman’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 24 (1942), 25–45.

Wormald, Patrick. The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, I: Legislation and Its Limits(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

———. ‘Archbishop Wulfstan and the Holiness of Society’, in Anglo-Saxon History: Basic Readings, ed. David A. E. Pelteret (New York: Garland, 2000), pp. 191–224.

James Titterington is a DPhil candidate the University of Oxford, currently working on a literary reassessment of Archbishop Wulfstan of York which considers all genres of his corpus.