Mercian Prose

Mercia, the largest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, included at its greatest expanse around the year 800 most of Southumbria: the West and East Midlands, East Anglia, the London area, the Thames Valley and Kent. It had expanded to these dimensions from its much smaller heartland in the West Midlands, at the border to Wales. There were multiple cultural centres within this greater Mercian area, with Worcester, Lichfield, Leicester, London and Canterbury perhaps the most important ones among them; these centres and other minor sites worked together to produce an extensive corpus of texts and manuscripts, particularly in the eighth and ninth centuries. These were written in several Old English dialects and subdialects spoken in Mercia, but the primary written language would in the earlier period still have been Latin. Old English took some time to emancipate itself as an equivalent means of expression, and this important process took place during the golden age of Mercian literature. It would indeed seem to be Mercia’s greatest cultural achievement to have experimented with innovative uses of Old English.

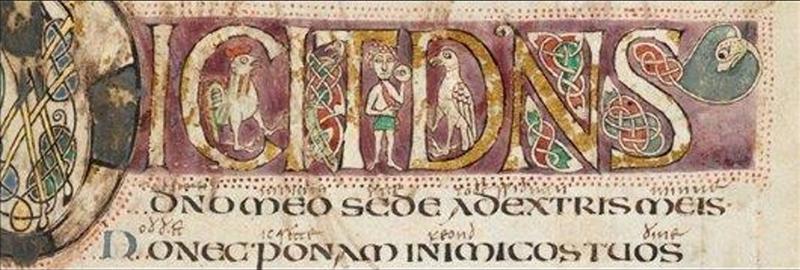

The most important cultural conquest made by the expanding Mercia in the eighth century was Canterbury, both a political and ecclesiastic centre of power, with its several religious houses and the archbishop’s see. It also represented a storehouse of ancient texts, including a wealth of Middle Eastern and European materials first introduced to England (and then also taught) by the late seventh-century intellectuals Theodore of Tarsus (modern-day Turkey) and Hadrian (of North African background). The legacy of this Canterbury School which they founded and where they practised a distinctive literal type of exegesis, laid the foundation for later Mercian prose production, and initially involved the compilation of glossaries and interlinear glosses. If glossaries were the early medieval equivalent of modern dictionaries and translation apps, the bilingual Épinal and Leiden Glossaries from the seventh and eighth centuries, and then the Vespasian Psalter Glosses from the ninth, all testify to the early Mercian need to engage with a worldwide Christian culture, Latin word for Latin word, with biblical texts from the Old Testament top of the reading list. The tiny precise script of the gloss in the Vespasian Psalter [Image 1] exemplifies clearly the hierarchy between it and the much larger ormamental biblical text that it glosses and which remains written in Latin.

[Image 1]

That some Mercian glosses are also found in books produced overseas (for example St Gall, modern-day Switzerland) shows how strong outward trajectories were, and the links with Rome and the Carolingian empire. Conversely, authors in Mercia had access to a wide range of incoming texts which were on a journey west along the silk road of literature, and on which Mercia was one of the endpoints. If Old English initially represented a side-by-side study tool for getting on top of the Latin language and the Christian heritage literature it conveyed, authors gradually became more ambitious. The first long Old English texts of the ninth-century such as the Old English Martyrology, the Old English Bede, and the Old English Dialogues of Pope Gregory can all be seen as standard handbooks of Christian worship, church history and divine interest in England. The texts speak to a wish especially for standardised provision of knowledge and religious resources that could be accessed where necessary throughout the Mercian realm. These new and somewhat more free-standing texts could travel without the Latin materials they were translated from, and some materials are beginning to look more like personal notebooks. With these first long Old English prose texts, Mercian authors also made important contributions to translation theory, in the first few centuries of English literary history, favouring a literal, ‘foreignizing’ style which still makes great linguistic demands on the Mercian reader who is really working with two languages and two cultural traditions simultaneously, the Old English and the Latin one. Numerous translation errors are apparent in these texts, and they have been also criticised for the ‘translationese’ feel of their prose style which stays very close to the Latin sources and which may seem awkward and fussy-sounding to us. But even if not yet very idiomatic in stylisic terms, they seem to have been remarkably effective in conveying Latinate content to all levels of proficiency in the Mercian readership.

The most reliable and earliest indicator of the greatness of Mercian translation can be found in neighbouring Wessex, where late ninth-century King Alfred is documented to have turned his mind to the cultural reputation of his own realm. Mercian scholars named as Plegmund, Werferth, Werwulf and Æthelstan were then headhunted to export their skills to Wessex. To judge from the later production of similarly long Old English prose texts from West Saxon production, it may have been exactly foundational works with Canterbury connections like the Old English Martyrology or the Old English Bede that may have sparked Alfred’s interest in emulating such productions. From around the same time, we have evidence for Mercian experimentation of Old English prose in charters and other administrative texts which was also adopted in West Saxon production. Repeated generational intermarriage between royal and aristocratic Mercian and West Saxon families completes the picture of adjacent cultures with free mobility of scholars, book materials and educational traditions. This must have been a powerful cultural alliance, especially at a time of Viking attacks which also resulted in a decline in the knowledge of Latin. Worcester may at this stage have come into its own as a rare haven of multilingual book-learning.

Although it is still difficult to arrive at a more nuanced chronology from within the Mercian period, there can be no doubt about the wide range of its range of literary genres which also included travel literature and mirabilia (Wonders of the East, Alexander’s Letter to Aristotle), medical literature (including Bald’s Leechbook), the early beginnings of vernacular life writing (sowing the seeds for the later and fuller Anglo-Saxon Chronicle), and texts of scientific and encyclopaedic content. This astonishing range of contrasting contents is nicely exemplified in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 196, p. 105 [image 2], where an entry in the Old English Martyrology preserves the earliest English mention of the scientific disciplines, including medicine, astronomy and geometry, and is immediately followed by the story of the Egyptian saint Chrysanthus who was divinely protected from five prostitutes by them miraculously falling asleep. The all-important educational impetus of late seventh-century Canterbury school culture, with its mix of arcane scientific information and saints’ cults from remote corners of Christendom, can still be felt in this ninth-century text and further down the centuries.

[Image 2]

Saints’ cults and their written expressions (hagiography) seem to have been a general priority for Mercian readers and worshippers, with favoured Mercian saints like Chad, Guthlac and Helena receiving particular attention in extensive free-standing prose and poetic saints’ lives and relic cults, with prose authors and poets (such as Cynewulf) showing similar interests. (To read about the prose "Life of Guthlac", click here). Mercian individuals were perceptive to potential miracles in their home environment, with angels frequently appearing as helpers and messengers and the intercession of hundreds of saints readily obtainable in Mercian hagiography. [Image 3, Lichfield Angel] It is important to note how much of this culture seems by that stage to have been standardised along the prescriptions of the Carolingian reform movement, with the worldwide pantheon of saints listed in the Old English Martyrology nicely aligned with the Rome-inspired, new, ecclesiastical centre at Brixworth, which may have served as a conference centre near the geographical mid-point of the kingdom. (To read about the Old English Martyrology, click here).

[Image 3]

Another specialisation was the production of prayer books and other ornate manuscripts, including those of the so-called Tiberius group, displaying a distinctive supra-regional style, and (as with other Mercian outputs) a good number of parallels with Irish book culture and learning. Concentrated more in the East Midlands is the extensive corpus of Mercian stone sculpture with its religious focus, which interestingly seems to peak and then diminish around the same time as Mercia’s literary production, in the late eighth to early ninth centuries. The driving intellectual and financial forces behind this wealth of material remain unidentified and could have involved royal or episcopal figures, to judge from later (and better documented) Alfredian parallels. Multidisciplinary research on both literary production and material culture could still yield more insights in this area, given the number of unanswered questions. Even just the visible parts of this iceberg are of impressive dimensions, and we can only guess at the extent of the lost material. One particular area where losses are paradoxically documented is that of homiletic prose, for which Mercia may also have provided early a forerunner: the later Blickling Homilies are thought to go back to Mercian prototypes.

It is important to remember that religious literature was likely composed and consumed in the same institutional environment as more secular genres, for example Germanic legend. A complaints letter from the year 797 to Unwona, Bishop of Leicester, chastises the state of the monasteries in his diocese. There, monks seem to have enjoyed religious and secular narratives and lifestyles in close proximity to each other, demonstrating at the same time the diversity of interests and strong reactions against it right in the heart of Mercia. What was clearly a lively popular culture of Mercian alliterative poetry preserved its appeal into later time, inasmuch as it seems to have been overwritten as the poetry of the neighbouring kingdom of Wessex, and then the larger unified kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England. The same fate befell some of the longer Mercian prose productions such as the Old English Martyrology and the Old English Bede which were reedited and reissued (we would now say) in modernised West Saxon formats once the separate kingdom of Mercia had ceased to exist in the later ninth century. Some conservative West Saxon authors seem to have longed for the authoritative information value or the old Mercian prose texts as well as for some poetic borrowings and mythmaking, perhaps in a way similar to the way Victorian literature is perceived in contemporary culture.

At its beginning, Mercian prose contributed some of the earliest examples of writing in the English language; at its peak it produced an enormous wealth of different genres, texts and manuscripts which transmitted heritage scholarship from earlier centuries and passed it on to neighbouring cultures such as Wessex and Anglo-Saxon England centuries later. Its greatest success, however, may well have been the Old English dialect of the London area (situated in Mercian territory), which in post-Conquest times came to form modern English as a world language.

Select Bibliography

The Mercian Network register lists some 120 manuscripts for which Mercian associations have been proposed, on the basis of a manuscript's origin or provenance within the Mercian political area, or suggestions of Mercian individuals being involved in the production of the given manuscript, or a combination of such details.

https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cr30/MercianNetwork/Primary%20Materials%20...

Texts

The Mercian Network register lists some 140 texts written in Old English and Latin, prose and poetry, including some 80 charters. Work to identify further productions with Mercian elements is ongoing.

https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/~cr30/MercianNetwork/Primary%20Materials%20...

Secondary Literature

Brown, Michelle P. and Carol A. Farr, ed. Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe (London: Bloomsbury, 2001).

Brown, Michelle P. ‘Mercian Manuscripts? The ‘Tiberius’ Group and Its Historical Context’, in Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, ed. Michelle P. Brown and Carol A. Farr (London: Bloomsbury, 2001), pp. 279-90.

—. ‘Female Book-Ownership and Production in Anglo-Saxon England: The Evidence of the Ninth-Century Prayerbooks’, in Lexis and Texts in Early English: Studies Presented to Jane Roberts, ed. Christian J. Kay and Louise M. Sylvester, Costerus ns 133 (Leiden: Brill, 2001), pp. 45-67.

Capper, Morn. 'Treaties, Frontiers and Borderlands: The Making and Unmaking of Mercian Border Traditions', Offa's Dyke Journal 5 (2023), 208-38.

Fulk, Robert D. ‘Anglian Features in Late West Saxon Prose’, in Analysing Older English, ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully and Emma Moore (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 63-74.

Gallagher, Robert. 'The Vernacular in Anglo-Saxon Charters: Expansion and Innovation in Ninth-Century England', Historical Research 91 (2018), 205-35.

Gem, Richard, ‘Architecture, Liturgy and Romanitas at All Saints' Church, Brixworth’, Brixworth Lectures ss 8 (Leicester, 2011).

Rauer, Christine. ‘Where was Mercian Spoken? Dialect and the Limits of Anglo-Saxon Mercia’, The Brixworth Lectures, second series, University of Leicester (forthcoming).

—. ‘Old English Literature before Alfred: The Mercian Dimension’, in The Age of Alfred: Rethinking English Literary Culture c.850–950, ed. Amy Faulkner and Francis Leneghan, Studies in Old English Literature 3 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2024), pp. 51-71.

—. ‘The Earliest English Prose’, Journal of Medieval History 47 (2021) 485-96.

—. ‘Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations’, Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik77 (2017), 541-58.

—. ‘The Old English Martyrology and Anglo-Saxon Glosses’, Latinity and Identity in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Rebecca Stephenson and Emily V. Thornbury (Toronto, 2016), pp. 73-92.

—. ‘Usage of the Old English Martyrology’, Foundations of Learning: The Transfer of Encyclopaedic Knowledge in the Early Middle Ages, ed. Rolf H. Bremmer jr. and Kees Dekker, Medievalia Groningana ns 9 (Leuven: Peeters, 2007), pp. 125-46.

—. ‘The Sources of the Old English Martyrology’, Anglo-Saxon England 32 (2003), 89-109.

—. A Literary History of Mercia: Scribes, Stories, Scholarship, c. 600-c.1100, Studies in Old English Literature (Turnhout: Brepols, in progress).

Roberts, Jane, and Alan Thacker, ed. Guthlac: Crowland's Saint (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2020).

Rodwell, Warwick, Jane Hawkes, Emily Howe and Rosemary Cramp. ‘The Lichfield Angel: A Spectacular Anglo-Saxon Painted Sculpture’, The Antiquaries Journal 88 (2008), 48–108.

Sauer, Hans, and Gaby Waxenberger. 'Old English: Dialects', in English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook, ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton (Berlin, 2012), pp. 340-61.

Seiler, A. 'Mæw or Meg ('Seagull')? Mercian Dialect Features in an Early Old English Glossary from the Continent', in Cultural Connections between the Continent and Early Medieval England, ed. Thijs Porck, Kees Dekker and Landor S. Chardonnens, Anglo-Saxon Studies 53 (Cambridge: D. S Brewer, 2025), pp. 227-50.

Vleeskruyer, Rudolf, ed. The Life of St. Chad: An Old English Homily (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing, 1953).

Wallis, Christine. ‘The Old English Bede: Transmission and Textual History in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts’ (PhD, University of Sheffield, 2013).

Wenisch, Franz. Spezifisch anglisches Wortgut in den nordhumbrischen Interlinearglossierungen des Lukasevangeliums, Anglistische Forschungen 132 (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1979).

Christine Rauer is Reader in Medieval English Literature at the University of St Andrews. She is currently writing a Literary History of Mercian Literature and has previously published on Mercian poetry as well as prose. She has, for example, edited the Old English Martyrology (Boydell and Brewer, 2013) and published on the literary world of the Beowulf-poet (Beowulf and the Dragon: Parallels and Analogues, Boydell and Brewer, 2000). She initiated the Mercian Network with its events and resources, and she directs the electronic database Fontes Anglo-Saxonici which charts the Anglo-Saxon network of authors and the English, European, African and Middle Eastern sources they used.